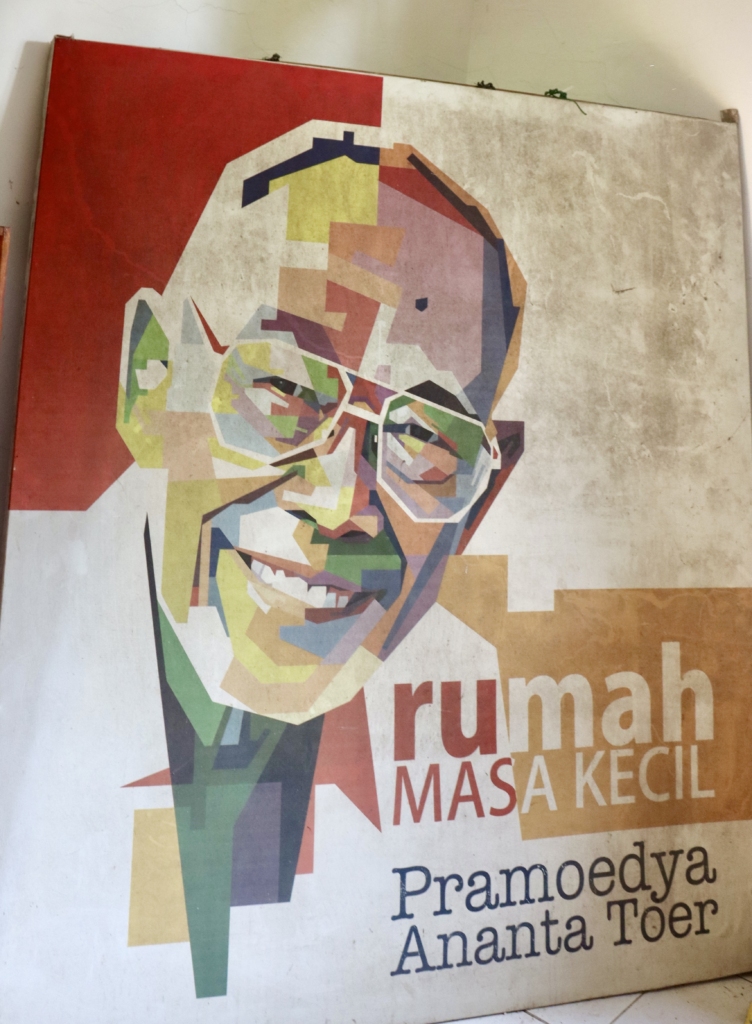

While I was in Blora, about 127 kilometers to the east of Semarang, the capital of Central Java Province, I did not want to miss visiting a historic building in the city which is the childhood home of Indonesia’s great author, Pramoedya Ananta Toer.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer was a master of Indonesian literature who was born in Blora in 1925. He was part of the 45 Generation literary movement, and his works include short stories, essays, and novels. Pramoedya was the only Indonesian author ever nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was nominated a total of six times. His outstanding works include the tetralogy consisting of Earth of Mankind, Child of All Nations, Footsteps, and House of Glass. He wrote this tetralogy while detained without trial on Buru Island in the Maluku Province by the New Order regime. Pramoedya is also the only Indonesian author whose works have been translated into 40 languages. Earth of Mankind was adapted into a film by director Hanung Bramantyo in 2019.

Pramoedya was detained for 14 years starting in 1965, 10 years of which were spent on Buru Island. He was detained by the New Order regime on the accusations that he was a communist because he had been involved with the People’s Culture Institute which was allied with the Indonesian Communist Party.

Today, Pramoedya’s body lies in the public cemetery of Karet Bivak in Jakarta. His childhood home in Blora stands as a piece of memory from his 81-year journey of life.

The Blora House

Accompanied by Eko Arifianto, one of the literacy activists in Blora, I visited a house located at the corner of Sumbawa Street, Jetis Neighborhood. Bounded by an iron fence, from the outside, the white-painted house looks simple. Eko opened the gate door. The yard of the house looks quite spacious. A pile of plastic sacks filled with dry trash were lined up against the yard wall. The doors and windows of the house are painted green while the edges are painted yellow.

The 300-square meter house is surrounded by a small terrace. The front terrace of the house is shaded by two barely worn out bamboo blinds. In the corner of the front terrace, there is a neatly stacked pile of used items. Two tubby goats lounged lazily on the terrace right in front of the door. Seeing visitors approaching, they didn’t want to move at all. Eko greeted the residents of the house.

In a short while, the door was opened. From inside emerged a white-haired and bearded man. Bare-chested, he wore knee-length pants. As soon as his eyes met Eko’s, a conversation broke between the two of them. Eko introduced me to the host, who was none other than Soesilo Toer, the younger brother of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who has resided in the house with his wife and son, Benee Susanto.

Eko Arifianto was not a stranger to Soesilo Toer. Both were active in the PASANG SURUT Institute for Social, Cultural, and Environmental Studies, with Eko as the secretary and Soesilo as the treasurer.

Just as I was sitting on the chair, Pak Soes – as he was affectionately called – began recounting stories about himself and Pram, the familiar nickname for Pramoedya.

Soesilo and Koesaisah—who lived in Jakarta—were the only two siblings left out of Pramoedya’s eight siblings. Pramoedya was the eldest child of Mastoer, a teacher and owner of the Boedi Oetomo School in Blora, and Siti Saidah. In the house built in 1923, the young Pram spent his childhood before wandering here and there as he grew older. The house had fallen into disrepair and was only renovated again in 2018.

Soesilo, born in 1937, still appeared energetic and had a sharp memory. “Pram started writing at the age 15, I was starting at 13, Pram was imprisoned for 14 years, and I was for 5 years,” he compared his fate to that of his oldest brother.

As he mentioned, Soesilo wrote various works including short stories, novels, books, biographies, and children’s stories. These works were displayed alongside Pram’s books and other translated books on a shelf in the living room. “I want to see the books,” I said as I was standing up from the chair. “Don’t just look at them, buy them,” Soesilo replied. “After all, I make a living by selling books,” he added.

Going to the Sovyet Union

Soesilo Toer’s destiny has been partly shaped by the fate of his eldest brother. Soesilo is the seventh child. In 1950, his parents moved to Jakarta from Blora and he attended Taman Siswa School. As he was grown up, Soesilo pursued his studies in the Economics Department at the University of Indonesia, then transferred to the Bogor Academy of Finance. Soesilo completed his diploma at the Bogor Academy of Finance.

When the Sovyet Union (now Russia) opened a scholarship program, Soesilo applied for it and he was accepted. Soesilo went to the Sovyet Union in 1962 after marrying his first wife, Suciati Atmo. He departed in the same year as B.J. Habibie, the then 3rd President of Indonesia, traveled to West Germany to pursue his further education.

Soesilo completed his master’s degree at Patrice Lumumba University and his doctoral studies at the Plekhanov Institute of the Sovyet Union in the field of politics and economics. Both universities are located in Moscow. His dissertation that criticized Marxism and Capitalism proposed an alternative third way called the Local Wisdom.

There was an incident that had fatal consequences for Soesilo’s future. In October 1965, the Indonesian Embassy in Moscow held an event to pray for the victims of the G30S (movement and political coup in Indonesia on 30 September 1965). Soesilo did not attend it because he did not get an invitation. He was then labeled a communist, a stigma that had a profound and lasting impact. To make matters worse, the nephew of Njoto (Vice Chairman of the Central Committee of Indonesian Communist Party) once visited his room. Then Soesilo’s passport was revoked even though he had not completed his studies. He lived without citizenship. The Sovyet Union government helped him by issuing a temporary ID card.

When he completed his PhD in 1971, Soesilo intended to return to his homeland. However, the New Order regime did not allow it. He was asked to make a routine mandatory in-person report to the Indonesian Embassy for two years. To support himself, Soesilo took on various jobs such as being a writer, translator, researcher, and doing manual labor.

Finally, he returned to Indonesia in 1973. However, as soon as the plane touched down in Jakarta and he disembarked, Soesilo was immediately arrested and detained for five years without due process or evidence of his wrongdoing. All because he was the younger brother of Pramoedya and studied in the communist Sovyet Union.

Scavenging is a Noble Work

Soesilo was released from detention in 1975 with an ID card stamped with ex-Tapol (political detainee). Not only Soesilo, but Pramoedya’s other siblings such as Prawito Toer and Koesalah Soebagyo Toer were also imprisoned by the New Order regime on charges of being affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), once again without any legal process. Another Pram’s brother escaped to Irian (now Papua) and assumed new identities.

“Koesalah (Soesilo’s older brother) received the Pushkin Medal from President Vladimir Putin for being the best Russian-Indonesian translator,” said Soesilo. The award was presented in 2015 through the Russian Embassy in Jakarta for Koesalah’s contributions in translating esteemed Russian literature works into Indonesian, such as those by Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekov, and Maxim Gorky.

With an ex-Tapol stamped ID card, Soesilo’s opportunities to earn a living were severely restricted. Similar to someone with a contagious disease, people hesitated to employ him due to fears of being associated with the PKI–a stigma from the New Order era. After being released, Soesilo lived in Jakarta and Bekasi taking odd jobs. In 2004, he and his second wife, Suratiyem, decided to return to Blora.

Back in his hometown, the stigma of being associated with the PKI has still stuck on him. His doctorate in economics and politics was of no use in job-hunting. The local community continued to marginalize him. Therefore, Soesilo didn’t hesitate to become a scavenger to support his livelihood. He sorted and sold usable recyclables. He usually scavenged with his motorbike in the evening. He used the profit from scavenging to buy chickens and goats for breeding. Soesilo was happy with his work, as he could truly be self-sufficient.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Child of All Nations

One of the rooms in the house was turned into a personal library named PATABA Library, an abbreviation of Pramoedya Ananta Toer Anak Semua Bangsa. The library was established as a contribution from the Toer siblings: Pramoedya, Soesilo, and Koesalah to the community in the field of literacy.

PATABA was founded when Pramoedya passed away on April 30, 2006. There were some paintings above the bookshelves in the room. The slightly dusty books on the shelves belonged to Soesilo. He used his own money to develop the library. The funds came from his book publishing and scavenging activities. The PATABA Library also organized other activities such as book discussions and cultural events.

PATABA Library began publishing books in 2009 under the name PATABA Press, starting with the publication of a bulletin. Subsequently, PATABA Press expanded by publishing books written by Pramoedya, Soesilo, or translations by Koesalah. PATABA Press is now taken care of under the PASANG SURUT Social, Cultural, and Environmental Studies Institute.

In 2018, there was a proposal from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Youth, and Sports of Blora Regency that Pramoedya’s childhood home in Blora would become one of the Literary Tourism Destinations in Blora Regency. However, it remained a proposal.

Soesilo offered to let me stay overnight at the house. Unfortunately, I had to continue my journey to another town. The brief encounter with him was indeed impressive, especially his spirit to build literacy awareness and love for reading among the community. “What’s difficult for me is to die,” he said, chuckling.