Our decision to visit Wotawati, a hamlet geographically located in Kalurahan Pucung, Kapanewon Girisubo, Gunungkidul Regency, Special Region of Yogyakarta, was quite spontaneous. “Because we’re heading to Gunungkidul,” was the agreement between Heni—my travel companion—and me before we departed. My interest in Wotawati was sparked by several social media posts mentioning that the hamlet receives only about 10 hours of sunlight per day.

Gunungkidul

Considering its far distance from Yogyakarta City, we departed in the early morning. Our car cruised smoothly on paved roads heading toward Gunungkidul Regency. We were greeted by a distinctive landscape of teak forests, rain-fed rice fields, and rural homes. Despite Gunungkidul being known as an arid region, it doesn’t look barren.

Along the way, we saw plenty of food stalls and small eateries—so as long as you have money, there’s no need to worry about hunger or thirst.

Upon entering Wonosari, the capital of Gunungkidul Regency, we stopped at a small kiosk selling tiwul and gathot—traditional Gunungkidul snacks made from cassava. These delicacies are rarely found outside the region.

The predominantly limestone soil in Gunungkidul is well-suited for growing cassava. Cassava has long played an important role for the locals. It is dried into *gaplek* as a staple food substitute for rice. Gaplek can also be processed into various snacks like getuk, tiwul, gathot, noodles, steamed cakes, and crackers. Gaplek is peeled and sun-dried cassava, which has a longer shelf life than fresh cassava.

After driving for about two hours, we entered Wotawati Hamlet. Our driver, Yahya, followed the road signs and directions provided by the locals. He had to be cautious, as some stretches of road were steep and winding.

The road leading to Wotawati is paved with concrete blocks, rather than asphalt, and is only wide enough for one car. The surrounding grass appeared dry and brown, while the green trees on the hills loomed tall. The midday sun was scorching, with clear blue skies overhead.

An Ancient Valley

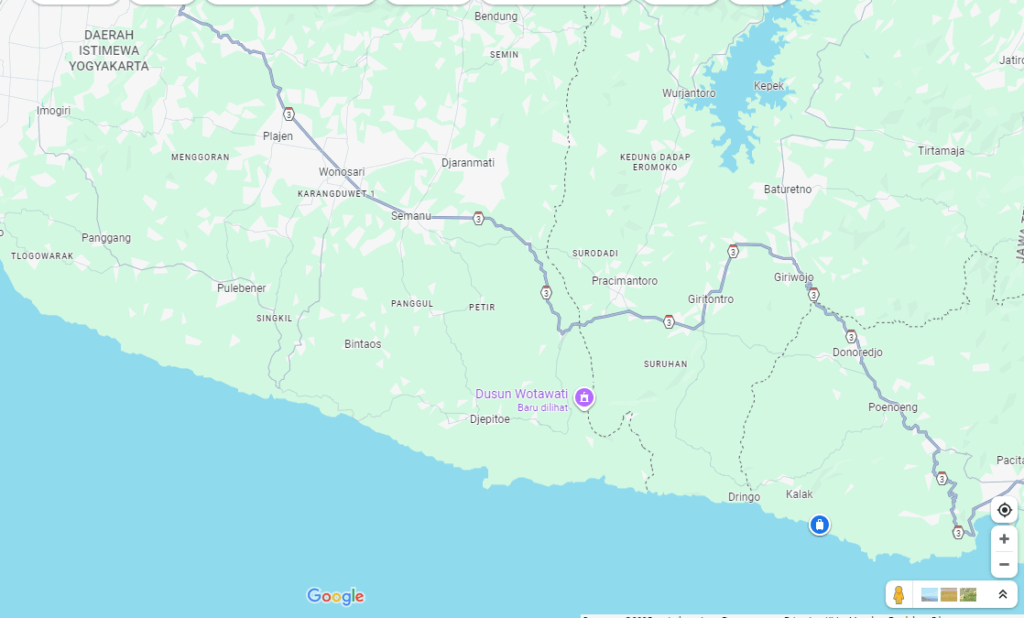

Located roughly 74 kilometers southeast of downtown Yogyakarta, this hamlet is situated in a valley that was once part of the ancient flow of the Bengawan Solo River. The headwaters of the ancient Bengawan Solo River originated in the hills of Wonogiri Regency (Giritontro Subdistrict), flowing through various villages before eventually emptying into Sadeng Beach in southern Gunungkidul.

Wotawati Hamlet is cradled between towering limestone hills. Because of this, sunlight only reaches Wotawati around 7:00 AM and disappears earlier, around 5:00 PM. However, during midday, the hamlet—projected to become a tourist village—gets full sunlight.

Upon arriving, we saw rows of terracotta-walled houses with matching façades, all appearing newly built. The homes were laid out in neat blocks, reminiscent of modern housing complexes. Every two to four houses, there was a connecting alley. These alleys were once water drainage paths built to prevent flooding. Now they are converted into concrete paths connecting parts of the hamlet.

Yahya was searching for a place to park when wek. We saw a house with a spacious yard. We asked him to turn into it—it had a small warung (shop) out front. The homeowner, who happened to be outside, kindly welcomed us.

A House in the Majapahit Style

We dropped by at the home of Mr. Tukijan, 60, and Mrs. Surati, 60. With the warmth typical of rural residents, the couple welcomed us, laid out a mat, and served snacks like bananas freshly picked from their garden and cassava crackers.

We chatted for quite a while at Mr. Tukijan’s home. The conversation took place in both Indonesian and Javanese, parts of which I could follow. My friend Heni, a native Javanese, would occasionally summarize the Javanese conversation for me. Despite the scorching weather, the gentle and cool breeze almost lulled me to sleep.

The newly built façades and walls of the house were part of a recent development. In 2023, the 83-household community of Wotawati received a Special Autonomy Grant (*Dana Keistimewaan*) from the Provincial Government of Yogyakarta, following approval of the proposal to turn the hamlet into a tourist village. The funds were used to draft plans, build a *pendopo* (traditional open pavilion), and construct walls and façades for the residents’ homes.

In 2024, 14 of the 79 houses were renovated using the funds. “It’s okay if someone doesn’t want their house renovated,” said Mr. Tukijan, whose yard was used as a storage site for construction materials. “In 2025, another 35 houses will be improved,” he added. His wife, Surati, also got involved in the project by preparing breakfast and lunch daily for the workers—of course, with compensation.

The architectural style chosen was a fusion of Majapahit and Mataram influences. According to stories from village elders, the ancestors of Wotawati’s residents were refugees from the Majapahit Kingdom. They once lived in Gua Putri, a cave situated at a high elevation. To find farmland, they had to descend from the cave and cross a small river. To do this, they built a powotan—a bamboo bridge wide enough for just one person. Legend says the name “Wotawati” originated from that bridge. Eventually, the settlers built huts and stayed in the valley.

A Remote Hamlet

Neither Mr. Tukijan nor Mrs. Surati knows exactly when the hamlet was founded. “I was born and raised here,” said Mr. Tukijan, who has one child. Before transportation was available, residents had to walk to their farms or neighboring villages. The isolation also led to intermarriage among neighbors. “He (Mr Tukijan) used to be my neighbor,” said Mrs. Surati in Javanese, chuckling.

The arid land made access to water difficult. Residents relied on rainwater since groundwater was hard to find. Each house has containers to collect rainwater, which is filtered and used for cooking and drinking. “Water from the regional water company is used for washing and bathing,” explained Mr. Tukijan.

The daily livelihood of Wotawati residents revolves around farming rain-fed fields and growing secondary crops, particularly cassava. From cassava, they produce snacks like gathot, tiwul, and getuk crackers. Gaplek is also a staple substitute for rice.

During our visit, another group of tourists was also exploring a house next door to Mr. Tukijan’s. At present, there isn’t much to see in Wotawati aside from the architecture, layout, and peaceful atmosphere reminiscent of settlements from the Majapahit and Mataram periods, as well as the local way of life.

By next year, the entire development project is expected to be completed, including roads, drainage, gazebos, gates, tourist information centers, and more. The seriousness of Wotawati’s transformation into a tourist village was underscored by a visit from Kanjeng Ratu Hemas, the wife of Sultan Hamengku Buwono X, a few months ago. “She came to inaugurate the pendopo,” said Mr. Tukijan.

A Tourism Village

Mr. Tukijan and Mrs. Surati fully support the idea of turning their hamlet into a tourist destination to increase income. They have even opened their home as a homestay. “One hundred thousand rupiah per person per night,” he said. According to the official website of the Yogyakarta Province, there will eventually be tour packages for visitors to Wotawati, including walking tours of the hamlet, farming with locals, and exploring the ancient Bengawan Solo River. Currently, there’s a traditional costume rental available for those who want to take photos in Wotawati.

With its unique location among limestone hills, fascinating history, and warm-hearted locals, Wotawati Hamlet is well worth a visit—whether you’re a nature traveler, culture enthusiast, or simply seeking a peaceful escape from city life.

Wotawati has opened its doors to the outside world. It’s a great alternative destination, especially when visiting the Gunungkidul region.